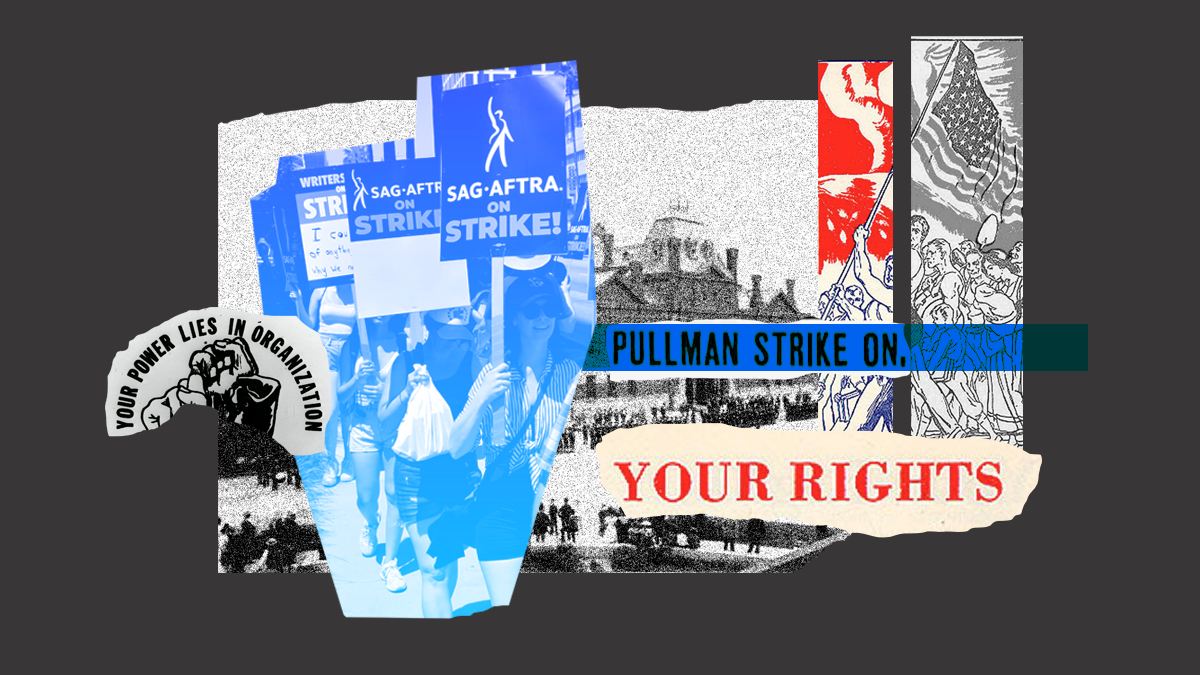

The Real History of Labor Day: When Workers Were Trampled

“The Strikers Throw Themselves on the Prairie, Preferring to be Trampled on by the Soldiers Rather Than Face Their Bayonets”

– Headline, New York Times, 1894

This is the real history of Labor Day:

Workers standing up for their rights—and being trampled for it.

In May of 1894, Pullman Palace Car Company, a railroad corporation, lowered their wages without lowering rents in their company-owned city. This was the last straw for already low-paid workers who, with these cuts, would likely starve to death.

By June 30, 125,000 workers across 29 railroads were on strike. During this crisis, President Grover Cleveland declared “Labor Day” a national holiday (afraid of losing the support of working-class voters). And eventually, Pullman agreed to hire the strikers back, under one condition:

They must pledge never to join a union.

Pullman had seen how powerful labor organizing could be—and they were terrified.

As all greedy corporations should be.

Through collective bargaining, union members have been able to win economic security for themselves and their families, including higher wages, access to affordable benefits, more stable schedules, greater ability to enforce workplace rights without retaliation, and the right not to be fired without cause.

It’s no wonder then that two-thirds of the American public approve of labor unions (an approval rating that has remained steady for years).

While unions are beneficial for all workers, union membership is especially important for women.

Women working full time who are union members typically make $214 more per week than women who are not union members—i.e., $11,128 more a year.

Over a 40-year career, that amounts to $445,120.

And while the gender wage gap persists even when women are unionized, women in unions are consistently paid wages that are not just higher but also more equal to men’s wages. It is also vital to note that unions are even more important for women of color—whose paid and unpaid labor uphold our economy, yet are forced to suffer under a system of racial capitalism at work.

Among full time workers, unionized Black women typically make 19% more per week ($157 more) than Black women non-union workers. And unionized Latinas typically make 36% more per week ($268 more). That’s $13,936 more per year, amounting to $557,440 over a 40-year career.

While these numbers might make it seem like we have come a long way since the Pullman strike, worker abuse still runs rampant today.

When asked about the ongoing Writers Guild of America strike, “The endgame is to allow things to drag on until union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses,” explained an anonymous executive. Homelessness is “a cruel but necessary evil,” said another insider.

These executives might just get away with their cruel and (unnecessary) evil—because the federal law designed to protect private sector workers’ rights to organize a union, the National Labor Relations Act, has been worn down over the years from relentless corporate attacks.

Take Amazon, known for crushing unions, as a prime example. When workers in Bessemer, Alabama, tried to organize a union, the company went so far as to change the traffic light pattern outside the warehouse to make it less likely that employees would be able to talk to union organizers.

Much is needed to support, strengthen, and protect workers’ right to organize. Federal legislation like the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, among others, will help to ensure working people and working women can come together collectively, without fear, to build strong unions—and better workplaces for all.

Learn more about the intersections between labor organizing and gender justice here.